Is There Bugger All Down Here?

An interesting and familiar science project is SETI – our search for extra-terrestrial intelligent life. But what of life on earth, how it arose, what defines it as intelligent, and what lessons can we take from our own intelligence into the SETI? Monty Python suggests, “pray that there is intelligent life somewhere up in space because there’s bugger all down here on Earth.” This article does not detail SETI but uses it as context and reviews some of the thinking about intelligent, or not, life on earth and what this could mean if we find intelligent life somewhere in our prayers.

There is no agreed definition of what life is or a proven mechanism that brought it about. The evidence suggests that life first appeared over 4bya in the young oceans just 300my after the earth was formed. For a vast period of over 3.5 billion years, life forms were simple, mostly single-celled or colonies and relatively homogenous until 550mya that changed with the Cambrian Explosion. This event saw a rapid increase in the complexity and diversity of all life forms and produced most of the major phyla present today. The causes are still speculative, possibly several small changes acting in concert could have created a biological big bang. An increase in oxygen levels, in turn initiating aggressive evolutionary arms races, seems most likely, however, an effective ozone barrier against solar radiation allowing for land animal development and the evolution of eyes might also have played parts.

The Cambrian Explosion set the scene that ultimately led to humans – fortuitous for us but probably not inevitable. The view in the rear mirror shows that while life began relatively quickly on the earth, and by implication on other worlds, complex life took far longer and therefore might not be inevitable on other planets with simple life forms.

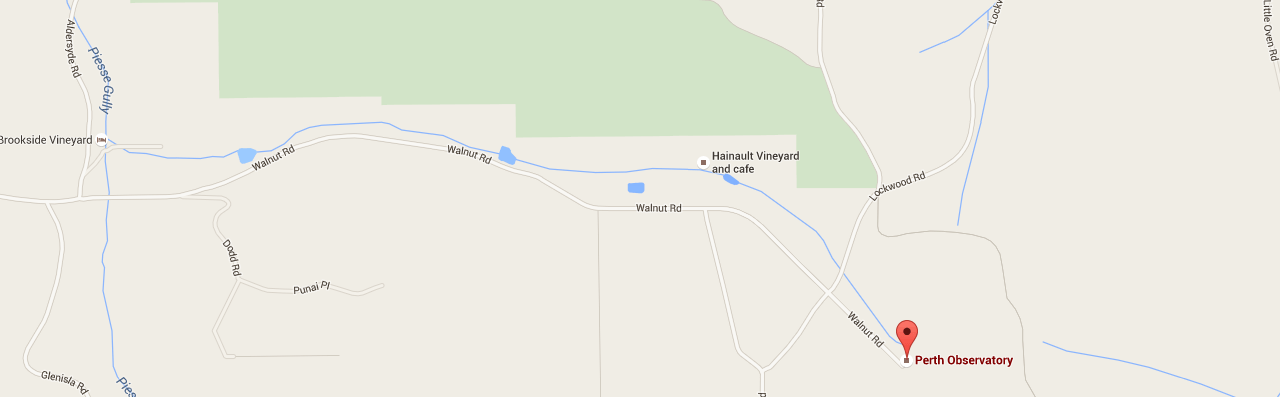

SETI and the associated discipline of Astrobiology have a few key assumptions and elements. Through a process of logical deduction, Drake’s Equation examines a hierarchy of probabilities from the number of stars (those with planets) all the way through to the odds where life is intelligent enough to broadcast radio signals. While Drakes principles are not controversial, the estimates of variables differ widely given how little we know at each stage in Drakes hierarchy. Drakes equation is also only applied to the Milky Way galaxy because although the principles apply to other galaxies, radio signals from other galaxies would be too faint for us to detect. Associated with this is the Fermi paradox that questions why there is no compelling evidence of life elsewhere given the impressive numbers coming out of Drakes equation.

The furry tail idea that porridge can be too hot, too cold or just right is the Goldilocks principle and analogous to an orbital zone around a star that is conducive to the evolution of life – that is, having a surface temperature ‘just right’ for liquid water.

The Goldilocks principle also applies at a galactic level. Certain parts of our galaxy (and other galaxies) will not be conducive to life because of factors like radiation or gravitational disruptions causing excessive impacts on the planet – once again, zones are required that are ‘just right’ for the development of life as we know it. The constraints imposed by a Goldilocks zone are given some added perspective by the Anthropic Principle, a convoluted tautology summed up by Stephen Hawking as, “the intelligent beings in these regions should therefore not be surprised if they observe that their locality in the universe satisfies the conditions that are necessary for their existence.” We are also now discovering organisms on earth living in very extreme environments, thereby effectively stretching earlier perceptions of the Goldilocks zone. We are also constrained by our own experience of “life as we know it” and tend to view SETI through this lens.

Our awareness of our place in the immediate and distant cosmic neighbourhood has only occurred in the past few hundred years with any valid observation and experience. Our first detection of external radio waves was less than a hundred years ago, and we intentionally transmitted our first radio signal less than 50 years ago. Voyager 1 left our solar system in 2012 and has another 40,000 years before its flyby with another star, so the chances of Voyager encountering alien travellers is remote.

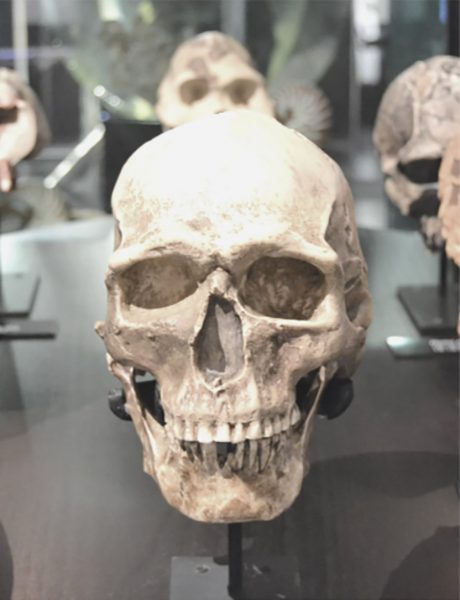

As for intelligent human life on earth, humans and chimpanzees shared a common ancestor somewhere between 6-8mya, and over the past 2my, there have been at least seven human species their time – how many did not prevail?

Our rise to shape and dominate certain aspects of the planet and most other species is only several 10’s of thousands of years and this is put down to the following probably familiar mechanisms: (Only most other species because something like hardy Tardigrades thrives in most extreme environments on earth, has done so for 500 million years and will probably outlive us all.)

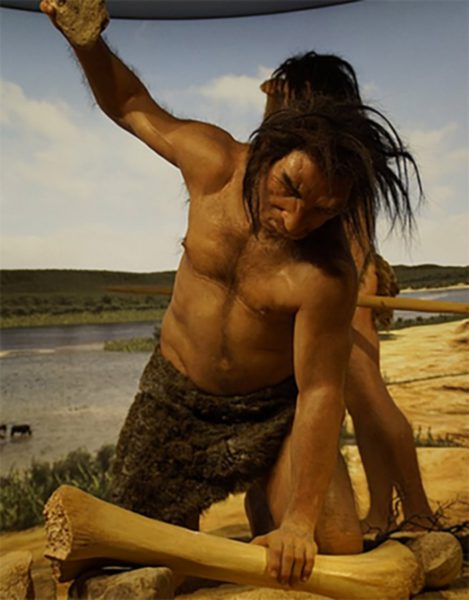

Fire: The use of fire for cooking and eating meat provided us with the necessary level of nutrition to feed a large brain. Cooking allows us to pre-process food making it easier and faster to absorb nutrients.

Verbal ability: An apparent mutation in our vocal chords allowed us to develop advanced speech giving us communication and co-operation that leapfrogged our social order. The addition of recording technology, from papyrus to digital, set in motion mechanisms and technologies with exponential consequences.

Grasping hands: Having grasping hands with opposable thumbs allows the use of tools. If speculation is correct that climate change that turned forests to grassland forced bipedalism on early humanoids, the hands should intuitively turn to more productive pursuits like tool use. Hooves, wings, fins, and paws don’t seem likely to lead to productive keyboard use. Possibly less familiar perspectives and ideas are those proposed by Edward O Wilson in his book, ‘The Social Conquest of Earth’.

Be terrestrial: Fire is a key catalyst for our transformation to uber apes and this means living on the land and not in the ocean. Regardless of how intelligent dolphins and octopuses are, they will never harness fire and as dexterous as tentacles are, grasping hands with opposable thumbs still manipulate tools better.

Be largish and terrestrial: Big brains need large bodies to support them. Despite Douglas Adams’ pan-dimensional creations in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, mice are unlikely to be resolving superstring theory any time soon, at best they will make nests or get elected onto the front bench.

Communication and Co-operation: These two fundamental ideas are implicit in our verbal ability.

In 1976 Richard Dawkins wrote a mind-bending book called, ‘The Selfish Gene.’ It proposed that the gene and not the individual is the unit of evolution by natural selection. While there were detractors, with this perspective Dawkins explained how altruism arose in populations, something Charles Darwin could not, with his original and highly controversial theory nearly 100 years earlier. What is less well known is the chapter on communication in ‘The Selfish Gene’. Here Dawkins notes that his own professor, Niko Tinbergen, proposed that communication is about the transfer of information. Dawkins turned this around, instead of saying that communication is about manipulation and not information transfer – the argument to support this being that natural selection favours individuals who successfully manipulate other individuals, regardless of whether this is to the advantage of the manipulated individuals.

Co-operation is another aspect defining human behaviour and accounts for much that humans are responsible for. Wiki optimistically tells us that we co-operate for mutual benefit – yet experience shows us, from the press-ganging sailors into merchant and military navies to business dealings and even in families, that co-operation has an unwilling and dark side.

The enlistment of young men into the great wars of the 20th century through draft laws and social doctrines of patriotism and heroism, all indicate an unknowing and possibly unwilling collective following the dictates of social institutions like religion, fashion, business and even science. It could be reduced to the collective social will achieving a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. This is not the same as saying that the entire group was co-operating, all the while singing, ‘jolly hockey sticks’. What is less clear is the mechanism behind the collective will of society. Let us suppose that humans have achieved such dramatic and organised outcomes because we are a cooperative species.

Despite this, brilliant and mutated minds like Newton arise and create a new path, and always facing massive opposition from the ruling paradigm. History reads like a stuck record to see that it’s virtually guaranteed that outliers will be socially punished. Galileo, Einstein (see ‘100 scientists against Einstein’), and Darwin are just a few of the outliers we now revere because they prevailed against the great unwashed of their time – how many did not prevail?

Between 2500-2300 BC the Mediterranean civilisation of Ionia stands as an unfulfilled scientific revolution. Isolated from other intellectual centres of the time, a collection of islands and city-states prevented a single concentration of power creating an intellectual melting pot of diversity and free inquiry. Around 540 BC a dictator – Polycrates – came to power, oppressing his people and waging war with his neighbours. Whilst achieving significant engineering feats, his regime is understood to have crushed the scientific enlightenment in the region.

Compared to other notable past civilisations, Ionia, unfortunately, left very few substantial traces. It appears they applied the beginnings of the scientific method and were on the brink of Darwinian, atomic and heliocentric discovery over 2000 years before it came to be re-discovered. Carl Sagan speculates, ‘If the Ionian philosophy had prevailed, we might have been travelling in the stars.’

The Ionians were somehow less constrained by a flat earth mentality due in part to the political structures arising from island geography. Is it possible that other innovative civilisations arose and collapsed with no trace whatever? Could the conditions of Ionia be consciously replicated in some way on earth? Are they happening in extra-terrestrial Ionias that we might one day contact?

A mantra of science states that it is an inevitable self-correcting process that leads to improved versions of

the truth. Yet it seems that human society has a stronger imperative than truth-seeking, that of seeking power, and the truth is the first casualty. While we search for ETI we should also vigilantly search for and foster intelligence on earth. Accepting that the Homo Sapiens capacity for blind conformance is necessary to ensure cohesion, minds like Einstein and they’re like are required to break the blind conformance and free science to advance independently of conventional thought. The irony and paradox of this are that it was the products of Newton’s mind that initiated the social momentum that effectively blocked alternatives for 250 years.

Humans have been social far longer than we have been human, and every group needs to protect its integrity from fractures caused by outliers. Does intelligent life require both the outliers acting as mental mutations and the blind momentum of the great unwashed or is this dysfunctional leapfrogging between innovative thought and blind compliance? Are these just inevitable facets of the human condition that achieve random and not necessarily progressive outcomes? Are we able to consciously harness this process, or are we and any intelligence everywhere resigned to serendipity?

If life is inevitably social wherever it arises, will it be subject to the same constraints that we have in every social species? The blind instincts of ants and bees that follow a proximal genetic program or the blind conformance of humans that follow an ultimate genetic program with a bolt-on for learning.