With the rapid growth of Perth in the 1890s due to the gold rush in Kalgoorlie, the need to adopt new technologies was brought home to the young colony of Western Australia. Along with the improvement in transport, communication systems, and electricity, Sir John Forrest, Western Australia’s first premier felt that it was very important for a growing colony to have new public facilities including an Observatory.

The aim of the Observatory was to provide the citizens of Perth and Western Australia with accurate time and weather reports as well as record seismic activity and astronomical observations of the southern sky.

A proposal for an observatory was first introduced to the State Parliament by the Premier in 1891 but failed to obtain financial backing.

In 1895, Forrest invited the Government Astronomer of South Australia Sir Charles Todd to visit Perth to help advise the government on the site and the equipment for an Observatory. While Kings Park was seen as the favoured location for new the Observatory, Sir Charles advised that Mount Eliza would be a better site due to the exposure to the distance from the city.

Todd also sent a letter to Forrest during this time stating that he believed his first assistant William Ernest Cooke had the qualities to be employed as the first government astronomer for the new Observatory and he was duly hired.

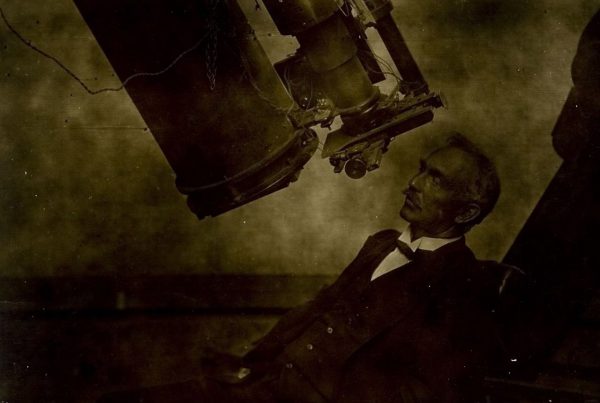

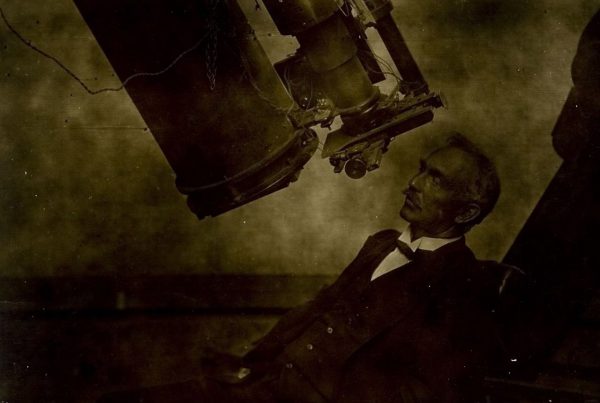

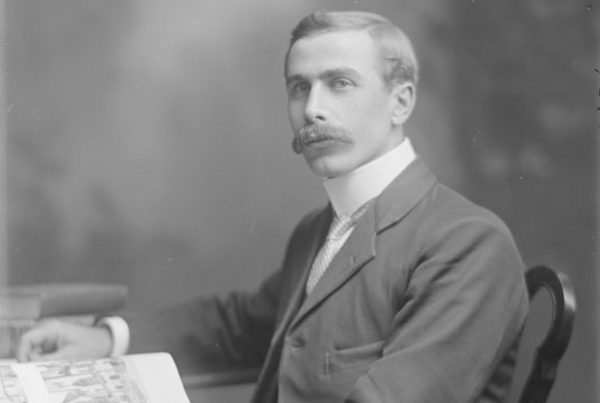

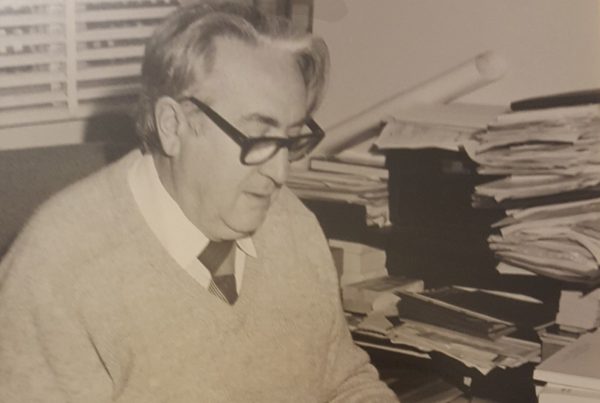

Ernest Cooke

1896 - 1912

Once appointed as Western Australia’s first Government Astronomer, William Ernest Cooke was tasked with designing the foundation stone. The stone featured the planets in their exact positions in the zodiac on the day of its laying by Sir John Forrest on September 29th, 1896. The laying of the foundation stone was celebrated as a grand civic occasion. The Observatory was completed at a cost of ₤6,622, more than double the estimated cost and 7 months late.

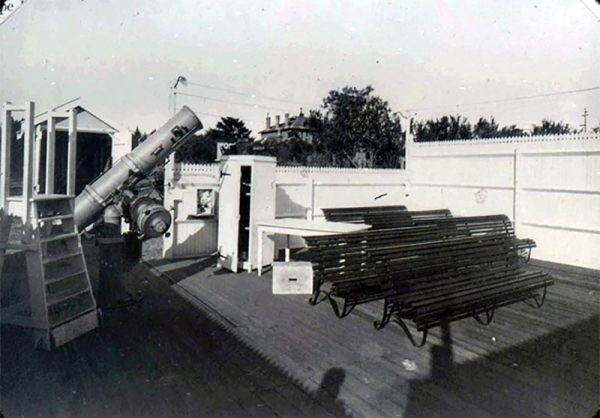

The Observatory consisted of the main office building, where the staff worked, and the Transit Circle Building, which housed the Meridian Telescope that provided accurate positions of the stars, allowing the astronomers to determine Perth’s latitude and longitude with greater accuracy. The final building was the dome, which housed the Howard Grubb-built Astrographic Telescope, used to map the southern sky, with research shared internationally.

During the Observatory’s first decade, under Cooke’s leadership, it achieved its goals of providing accurate time and weather reports. The Observatory provided regular time signals to shipping at Fremantle, the state railways, and the telegraph system, and controlled public clocks in Fremantle and Perth. Between 1901-02, a time cannon was set up on the eastern slope of the site and would fire daily for a 1 pm time signal. but it was taken away after repeatedly scaring people and causing someone to go into cardiac arrest passage of cyclones from the North-West into the interior, publishing cyclone forecasts for the first time.

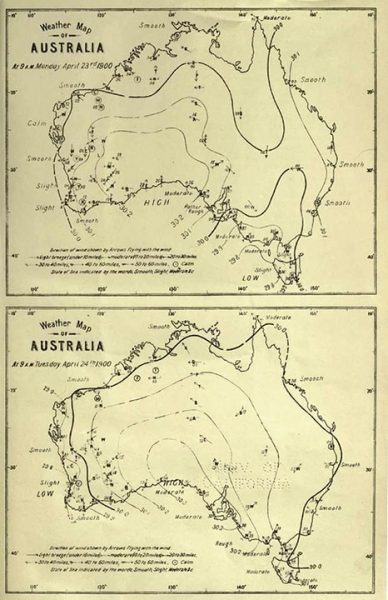

Weather forecasts for the state were also produced by Cooke and displayed in prominent places in the city and published in the press until 1908 when the Federal Government created the Bureau of Meteorology. Cooke’s interest in the development of low-pressure zones led him to study weather records from the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, and Mauritius, hoping to associate weather events there with later events in Australia. He analyzed and mapped the

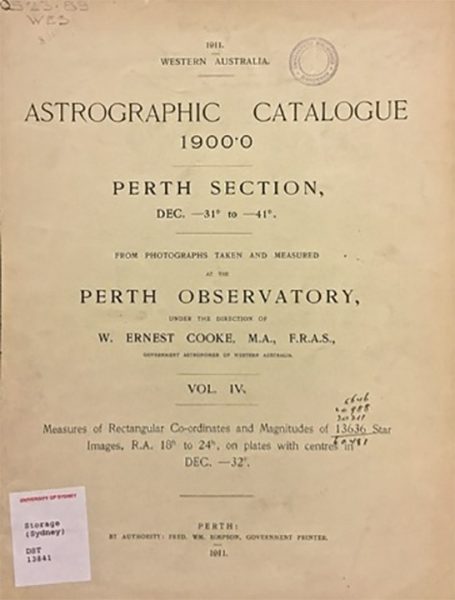

In 1900, the Perth Observatory was invited to contribute to the International Star Cataloguing and Mapping Program, along with 17 other observatories around the world. Later, in 1907, a Catalogue of 420 stars was published.

Cooke established the exact latitude and longitude for the Observatory in 1899, and it also provided tide tables for the north-west ports and astronomical information, including tables of sunrise and sunset, for the general public, press, and business.

The Observatory was open to the public every Tuesday evening for public viewings of the equipment and lectures in astronomy. By 1912, visitors’ evenings were so popular that a 12-inch Calver Telescope was purchased to meet the demand. This device was erected near the main entrance, and a series of regular bi-weekly receptions were held.

Cooke resigned in 1912 to take up an appointment with the Sydney Observatory. His position was not officially filled until 1920 when Harold Curlewis was promoted from Acting Government Astronomer to Government Astronomer.

Harold Curlewis

1912 - 1940

In 1912, Cooke resigned from his position as Government Astronomer in New South Wales to join the Sydney Observatory. However, his role remained unfilled until 1920, when Harold Curlewis was promoted from Acting Government Astronomer to Government Astronomer.

The delay in appointing Harold was due to the state government’s lack of support for the Observatory. The government had even applied to the commonwealth government in 1902 to take over the Observatory’s management. Although the Commonwealth rejected the proposal, it did assume responsibility for the meteorological work in 1908, establishing new offices in the city.

In late 1912, the State Government threatened to close the Observatory and proposed that the Commonwealth take over its operations. However, astronomers in England and elsewhere strongly protested against its closure, and negotiations with the Commonwealth continued. The State Government eventually decided to keep the Observatory in 1928.

In 1920, Curlewis collaborated with George Dodwell, the Government Astronomer of South Australia, to determine the positions for marking the Western Australian border at Deakin.

In 1921, they traveled by the State Ship, MV Bambra, to a point on Rosewood station near Argyle Downs, where they used wireless radio time signals and other methods to fix a position for the Northern Territory border with Western Australia. These efforts led to the formation of Surveyor Generals Corner in 1968, where the state boundaries of South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory converge.

In 1922, an expedition was undertaken to photograph a solar eclipse and measure the bending of light as it passed by the sun, which was required to test Einstein’s newly proposed Theory of Relativity. Previous expeditions had failed due to various reasons, including bad weather and instrumental deficiency.

The most favourable site for the expedition was a spot on Eighty Mile Beach on the northern coast of Western Australia. Professor Alexander Ross of the University of Western Australia advocated strongly for the expedition to take place, and it resulted in the most accurate measurements to date.

The scientific personnel for the expedition consisted of parties from England, the US, Canada, India, Perth Observatory, New Zealand’s Government Astronomer Charles Adams, and J.B.O. Hosking of Melbourne Observatory. The US team’s telescopes worked perfectly, and the plates developed on the spot showed excellent images. After meticulous research of the plates, the results were announced in April 1923, which confirmed Einstein’s theories.

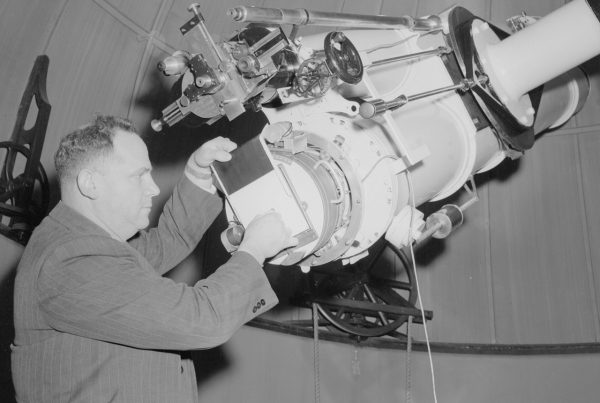

Hyman Spigl

1940 - 1962

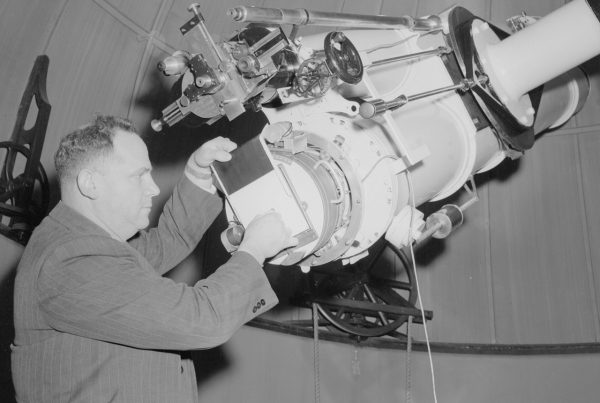

Harold Curlewis was succeeded as Government Astronomer by Hyman Solomon Spigl, who served in the role from 1940 to 1962. Spigl came from a surveying background and was tasked with rebuilding the post-war-ravaged Observatory, which had been reduced to only two astronomy staff during the Great Depression.

Spigl rejuvenated the time service and seismology services and got the Observatory involved in the International Geophysical Year by installing a Markowitz Moon camera. He also restarted publications for the Royal Astronomical Society. Spigl’s efforts led to the completion of the Astrographic Catalogues, and between 1949 and 1953, the Edinburgh/Perth Astrographic Catalogues were published, which recorded the positions of 139,000 stars.

In recognition of his achievements, Spigl was awarded a Gledden Travelling Fellowship by the University of Western Australia in 1958, which allowed him to travel and explore astronomy in the US, UK, and Europe.

As a result of the 1955 Stephenson-Hepburn Report, which identified the Observatory site as a potential location for government offices, Spigl actively searched for a new site for the Perth Observatory. However, unfortunately, he passed away on August 20th, 1962, and was succeeded by his assistant, Bertrand Harris.

Bertrand Harris

1962 - 1974

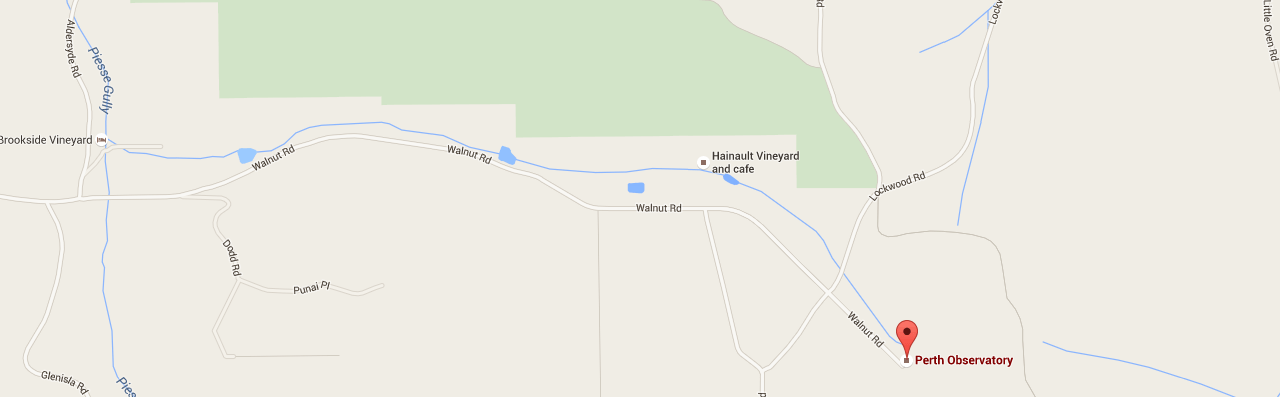

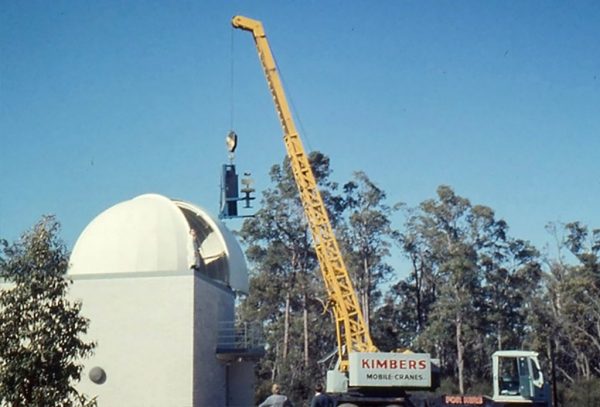

Harris, who had served as Hyman Spigl’s assistant since 1957, assumed the position of Government Astronomer at the Perth Observatory after Spigl’s passing in 1962. Harris was faced with the challenge of overseeing the relocation of the Observatory to its new site in Bickley. The clearing of the land began in February 1964, and the new Observatory was constructed at a cost of $600,000. On September 30, 1966, 70 years and one day after the laying of the foundation stone of the original Observatory, the new facility was opened by the Premier, David Brand.

|

|

|

During his tenure, Harris oversaw the installation of a meridian telescope, part of an expedition by astronomers from the Hamburg Observatory in 1967. This effort contributed to the international Southern Reference Stars program, which yielded a revised, more comprehensive meridian catalogue of the Southern Hemisphere. The resulting Perth 70 meridian catalogue mapped the position of almost 25,000 stars.

|

|

|

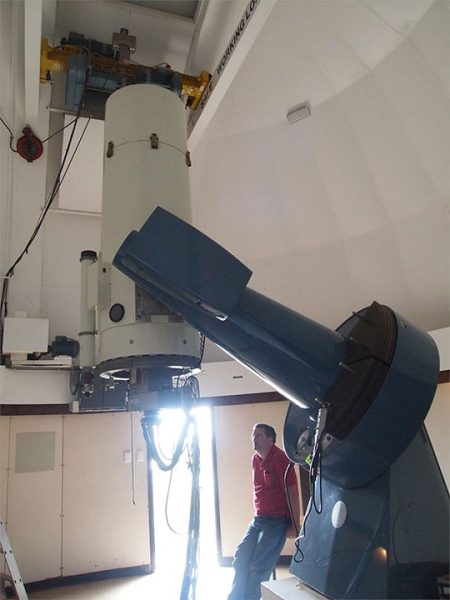

Harris also arranged for the refurbishment and relocation of the Astrographic telescope, which had been in storage since 1963. It resumed observations in 1968. In 1968, the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona sent a 24-inch Boller and Chivens telescope to the Perth Observatory as part of the International Planetary Patrol Program, which included seven telescopes around the world (including Mount Stromlo) and was sponsored by NASA. The goal of the project was to gather 35mm photographic data on the atmospheric and surface features of Solar System planets.

While successful in increasing the staff numbers at the new Perth Observatory and transitioning its focus to scientific research, Harris also reinstated public tours in 1966 and continued time and tide services for Western Australia. The Perth Observatory Meridian team carried on and expanded the work of the German team, resulting in the Perth 75 meridian catalogue, which mapped the positions of nearly 2,600 stars.

Harris was responsible for the August 1973 IAU Symposium No. 61 in Perth on “New Problems of Astrometry.” Although he passed away at the early age of 49, like his predecessor, he elevated the status of the Perth Observatory to a well-respected scientific institution within Australia and internationally.

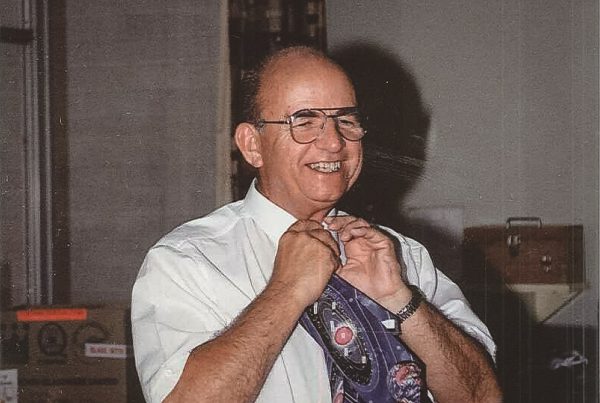

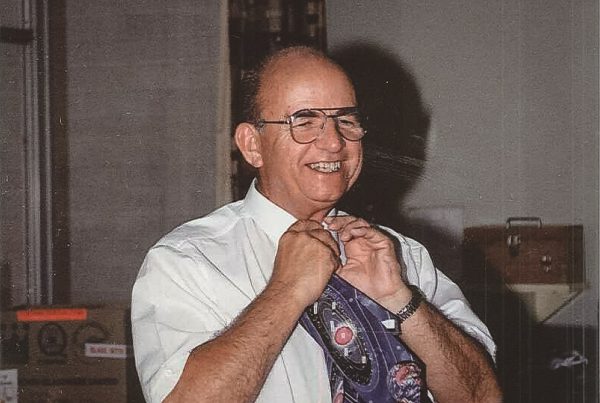

Dr Iwan Nikoloff

1974 - 1984

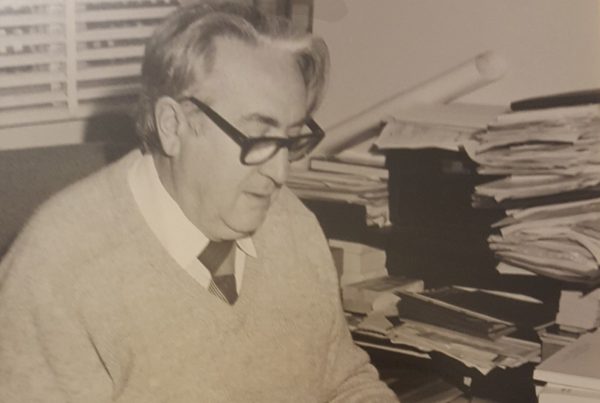

After Harris passed away at the end of 1975, Iwan Nikoloff took on the role of Acting Government Astronomer, which became official in 1979. Nikoloff had fled his home country of Bulgaria, which was under the Iron Curtain, and arrived in Australia in 1964, where he was appointed as an Astronomer Grade II at the Perth Observatory on May 1 of the same year. His previous experience enabled him to work on the Observatory’s astrograph, and he also set up and calibrated the recently acquired Zeiss plate measuring machine.

When the Perth Observatory was relocated from Bickley, Nikoloff’s surveying skills were heavily used to establish the new Observatory in 1965. From 1969 to 1971, Nikoloff collaborated with the German Hamburg Observatory meridian circle telescope expedition on the Perth 70 catalogue before the expedition astronomers returned to Germany that Christmas.

In 1971, the State Government provided funding, and negotiations were made for the loan of the Hamburg telescope. Nikoloff was put in charge of the newly formed Perth Observatory Meridian Section and started an observing program of FK4 and FK4 Supplementary stars that would result in the Perth 75 catalogue of 2,549 stars. The catalogue not only extended the well-revered Perth 70 catalogue but also provided valuable Southern Hemisphere information for the construction of the new FK5 reference frame sought by the international astronomical community.

When Nikoloff became the Government Astronomer, he handed over the Meridian Section to Dennis Harwood but remained involved in the construction of the subsequent Perth 83 meridian catalogue. He also kept himself busy with daily administrative duties and continued to observe on all the Observatory’s telescopes at night and on weekends.

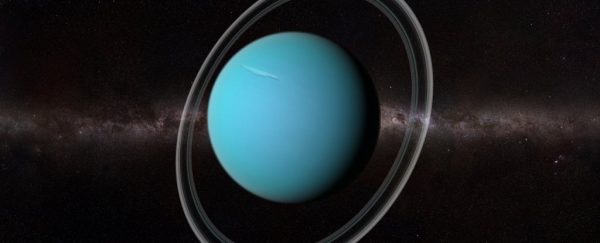

In 1977, Perth Observatory hosted Dr Bob Millis from Lowell Observatory in Arizona, who had come to Perth to study the occultation of the star SAO158687 by Uranus. NASA sent the Kuiper Airborne Observatory to Perth to study the occultation as well. By monitoring the intensity of the starlight from SAO158687 as Uranus passed in front of it through a photometer, both the Kuiper Airborne Observatory and Perth Observatory were hoping to study the atmosphere of Uranus.

Although Perth was slightly too far north to witness the occultation, Bob Mills and Dr Peter Birch, an astronomer at Perth Observatory, were able to record the disturbance of the star’s light five times before the Kuiper Airborne Observatory arrived back in Perth. The recording that the Perth Observatory took helped confirm that Uranus had rings, which was a significant discovery since, up until that time, astronomers believed only Saturn had rings.

With the closure of research at the Sydney Observatory in 1982, Perth Observatory became the last state-funded observatory in Australia. Nikoloff maintained a good relationship with the University of Western Australia and was a Foundation member and Fellow of the Astronomical Society of Australia, a life member of the Astronomical Association of Western Australia, and a member of the IAU’s original Commission 8 (Astrometry) and I (Fundamental Astronomy).

He continued the Observatory’s public information services and tours until his retirement on January 4, 1985. Sadly, Nikoloff passed away on April 8, 2015, at the age of 93.

Michael Candy

1984 - 1993

After Dr Iwan Nikoloff’s retirement, Michael Candy became the first Director of the Perth Observatory. Candy oversaw the observatory’s vital role in researching Comet Halley in 1986 as it returned to the inner Solar System to orbit the Sun. The comet approached the Earth from the north, disappeared behind the Sun, and then reappeared in the southern skies, inaccessible to the northern hemisphere.

In 1969, Candy was offered the Director position of the British Astronomical Association, but he declined the offer because he planned to emigrate to Australia that year. Upon arriving in Australia on the 12th of May, 1969, he joined the Perth Observatory as an Astronomer Grade II and in November that same year, Candy took over the Perth Observatory Astrographic telescope from Dr Nikoloff.

Candy positioned the Perth Observatory as a leading centre for southern cometary astrometry by 1972, ranking 9th in the world for producing cometary positions. He introduced new photographic glass plate processing practices to increase the limiting magnitude of observable objects from the 14th to the 19th. The new processes recovered five comets, leading to the Observatory’s 2nd place ranking between 1973 and 1977 and 4th place between 1978 and 1984. These achievements earned Candy the prestigious Merlin Medal of the British Astronomical Association in 1975. Under his direction, the Perth Observatory discovered over 100 new asteroids and contributed a significant number of observations to the Minor Planet Center.

Candy continued the publication of the Perth Observatory’s communication on comets and minor planet positions, initiated by former Government Astronomer Bertrand Harris. He published Communication No. 2, 3, 4, and the last, Communication No. 5, in 1986.

In 1979, Candy’s astrometric abilities and contributions earned him the Vice President position of the International Astronomical Union, Commission 6, which he held until 1982 when he was elected President for a 3-year term. He also became a working member of the International Astronomical Union Commission 20 until 1988 – Positions and Motions of Minor Planets, Satellites, and Comets.

Perth Observatory staff took positions of Comet Halley with the Astrographic telescope in 1986. The positions were used to fine-tune the positions of the comet for the armada of spacecraft heading for the comet. 10% of all Earth-based positions of Comet Halley to get ESA’s Giotto spacecraft to the comet were taken from Perth. Astronomers from the University of Maryland in the United States also visited the Observatory to use its telescopes and the first digital camera used in Western Australia to study the physics of the comet.

In 1987, the future of Perth Observatory was again thrown into doubt when the Minister for Works and Services, Peter Dowding, asked the Bickley astronomers to ‘justify’ their research projects and their annual budget of $750,000. However, support for the Observatory’s work flooded in from local and interstate scientists.

To better inform the public about the valuable work carried out by the Observatory, its staff provided night tours using the Observatory telescopes in the late 1980s. Within a short time, the program had a high demand. Additionally, school groups and special interest groups were catered to during the day.

In the early 1990s, the Lowell telescope was equipped with a special camera and automation, making it one of the first telescopes in the southern hemisphere to be fully computer-controlled. The Observatory staff and academics from Curtin and Murdoch Universities and the University of Western Australia undertook this work.

Mike Candy had an illustrious career as a councillor and president of various astronomical societies. He served as a councillor of the Astronomical Society of Australia and the Royal Society of Western Australia from 1988 to 1990, and also held the position of president of the Royal Society of Western Australia in 1989.

Candy’s retirement in 1993 was also compulsory, but he continued his work at the Perth Observatory on several projects. These included the study of the eclipsing binary FO Hydra, the development of a comet hunter telescope, and the creation of a new theory on comet origins and evolution. He also analyzed the lost comet Gale, and compared a South Australian comet discovered in 1979 with one discovered in 1770.

Sadly, Mike passed away less than a year later, on the 2nd of November 1994. However, his contributions to the field of astronomy were significant and were honored with the naming of Minor Planet 3015 Candy in 1980. After his death, the comet hunting telescope at the Observatory was also named after him as a tribute to his remarkable career.

Dr James Biggs

1994 - 2010

In 1994, James Biggs assumed the role of Government Astronomer and initiated the Observatory’s transition into the digital era by introducing CCD imaging and robotic telescopes.

As part of the Department of Conservation and Land Management, Perth Observatory enjoyed improved computer network support, enabling remote control of telescopes by networking computers.

The Observatory’s centenary on 21st September 1994 was a momentous occasion that brought together Australian and international astronomers, past staff, and distinguished guests, including Premier Richard Court. To commemorate the occasion, Dr Joseph Dolan from NASA’s Goddard Flight Centre delivered a Centenary lecture on the Observatory’s lawn, and a series of “car park astronomy nights” were held around Perth City during the year’s first quarter moon.

To assist with night tours, the Perth Observatory Volunteer Group was established in 1996. By 2001, the POVG had grown in numbers to the point of incorporation.

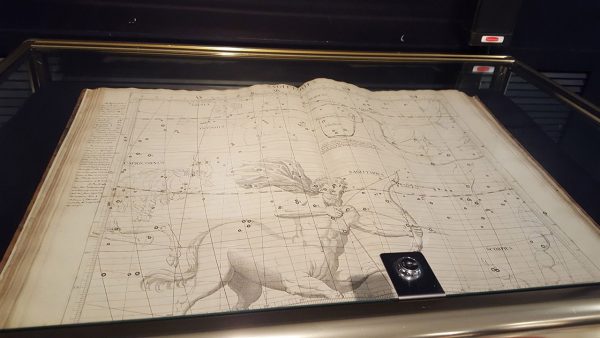

In 2001, Ethelwin Flamsteed Moffatt, a descendant of John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal and creator of “Atlas Coelestis,” donated one of the ten believed to exist in the world to the Perth Observatory.

In 2005, the Perth Observatory was added to the Register of WA Heritage Places, reflecting its significant contribution to Western Australian history and heritage.

By 2007, the Observatory had installed its first Internet telescope, with students frequently utilizing the new technology. Later on, a second telescope was added, making the Observatory one of the world’s most powerful robotic telescope systems at the time.

Dr Ralph Martin

2010 - 2013

With funding for research at the Perth Observatory declining, with the Western Australian Government shifting its focus from observational astronomy towards radio astronomy projects such as the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) and the now cancelled Gravity Wave Centre in Gingin. Jamie resigned in 2010, and Ralph Martin took over as the Director until 2013 when the position was eliminated as part of the research closure.

Starting in 2009, the Perth Observatory Volunteer Group (POVG) had begun leading public tours previously handled by Observatory staff. These tours continued even after the last permanent staff were made redundant in 2015.