Earth's big brother continues to protect the inner Solar System

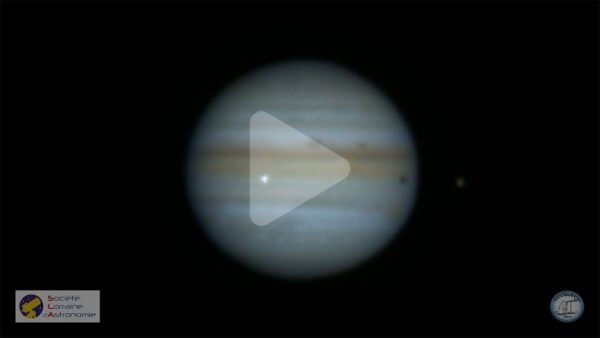

On the night of September 13th, 2021, across the globe, professional and backyard astronomers alike were setting up for an evening of planetary viewing. Unbeknownst to them, this evening would be special. At 22:39:27 UCT a bright flash was detected at a latitude of 106.9° and longitude +3.8° in the Jovian atmosphere lasting for a total of two seconds before fading and leaving no trace.

Brazilian amateur astronomer Jose Luis Pereira captured the impact whilst taking video footage of the planet for the DeTeCt program. The DeTeCt program allows amateur astronomers to upload videos of planets, and the software will scan for possible impacts allowing data to be collected and reviewed on such events. It wasn’t until the morning of the 14th that the software had finished scanning the images from the night before and the results were ready for viewing. Indeed, there was an impact record in Pereira’s first video of the night.

The footage was sent to Marc Delcroix of the French Astronomical Society who verified the impact. This sparked a wider global request for data obtained that evening for further review and assessment of the impact.

Later assessment of the light curves created by the impact showed that a rocky fragment possibly as large as 20m was likely the culprit. Just over a month later, on Friday 15th October, skywatchers in Japan reported another bright flash this time in the planet’s northern hemisphere. This impact reporting was again corroborated by the team at Japan’s Kyoto University.

Jupiter orbits close to the asteroid belt and due to the planets great mass the gravitational pull is strong. Therefore, events like this are not as rare as you may think. A 2013 study led by Richard Hueso Alonso, of the University of the Basque Country in Spain, estimated that Jupiter is hit by objects ranging from 5m to 20m between 12 and 60 times a year.

One of the most famed impacts was in July 1994 when pieces of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 that broke apart in 1992 blazed into Jupiter’s atmosphere and collided leaving dark scars in the planet’s atmosphere. This was the first time a collision of two solar system bodies could be observed from Earth. Over the space of a week, 21 separate fragments of the comet collided into the atmosphere.

There is some conjecture between astronomers as to whether Jupiter acts as a shield, capturing objects from the outer solar system and an asteroid belt protecting the earth from impacts. A recent school of thought is that Jupiter could also be catapulting some objects closer to earth’s orbit.

Here on Earth in 2013, an asteroid estimated to be 18 meters across broke up over the remote city of Chelyabinsk, Russia causing property damage and injuring many people. This event along with the gathering data from other impacts in our Solar System turned the spotlight onto the need for more research into near-Earth objects. In 2016 NASA implemented the Planetary Defence Coordination Office (PDCO) to work with international counterparts and monitoring observatories to aid in the early detection of potentially dangerous asteroids and comets.

NASA reported in 2011 that 90% of the largest asteroids 1km in diameter and above near to earth had been detected. This however didn’t cover the smaller asteroids that still pose a potential risk. Therefore, one of the main objectives of the Planetary Defence Coordination Office is to “monitor and ensure early detection of potentially hazardous objects whose orbits are predicted to bring them within 0.05 AU of the Earth; and of a size large enough to reach Earth’s surface that is, greater than approximately 30-50 meters”.

NASA’s PDCO has recently launched an exciting planetary defence mission as a project of the agency’s Planetary Mission Program Office. The ‘Double Asteroid Redirection Test’ mission (DART) launched on the 24th November 2021 from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. This mission is managed by Johns Hopkins APL for the PDCO with its main objective to redirect an asteroid using kinetic energy to impact it.

Earth-based telescopes will then measure and model the outcomes to help develop our defence systems should we ever need to use them. It will take 10 months for DART to arrive at asteroid Dimorphos and the collision will take place September – October 2022. So, watch this space!