Ancient Women Astronomers Series

Hildegard von Bingen was a remarkable woman especially considering she lived in the 12th century. She was born in Germany, a 10th child (a tithe) to a noble family. As was customary with the tenth child, she was dedicated at birth to the church, a common practice in those days.

She rose through the ranks of the church and in 1136 she was elected a magistra (Latin for teacher) by her fellow nuns. She claimed to have suffered visions from early childhood which continued throughout her life. This apparent connection with the divine helped her circumnavigate the mediaeval church traditions at that time and enabled her to preach and get involved with philosophy and the sciences.

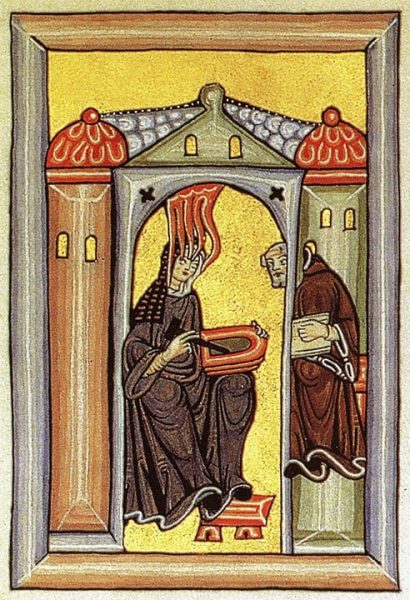

Illumination from the Liber Scivias showing Hildegard receiving a vision and dictating to her scribe and secretary. Most of her works involve visions and in 1141 she received a vision telling her to write down “that which you see and hear” which she dutifully followed, beginning what would be her first book, Liber Scivias, (“Know the way”), which she would conclude in 1151.

In 1148, a committee of theologians, at the request of Pope Eugenius III, studied and approved part of Scivias. The Pope then authorised Hildegard to preach in public. It was extremely unusual for medieval nuns to leave their enclosed orders or to make public statements, but Pope Eugenius III was consumed with his battle against the Cathar heresies ( Roman Catholics refer to Cathar belief as “the Great Heresy” though it appears that the official Catholic position is that Catharism is not Christian at all). In this regard, the Pope needed Hildegard’s help. She took her preaching very seriously, calling on the Holy Roman Emperor and church leaders to reform their faith and halt abuses. Such was her fame that she became known as Sybil of the Rhein. People went to listen to her words of wisdom or to seek cures or guidance.

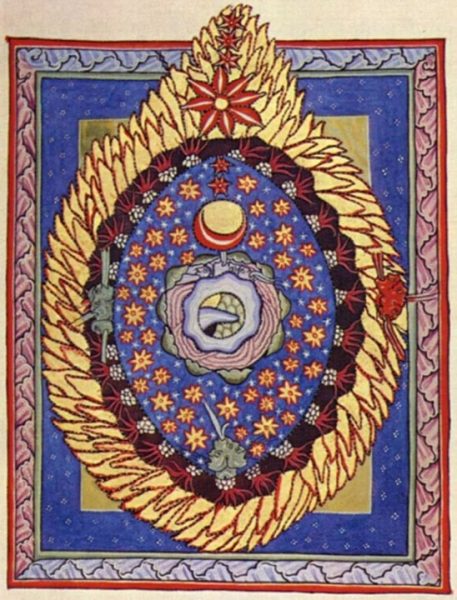

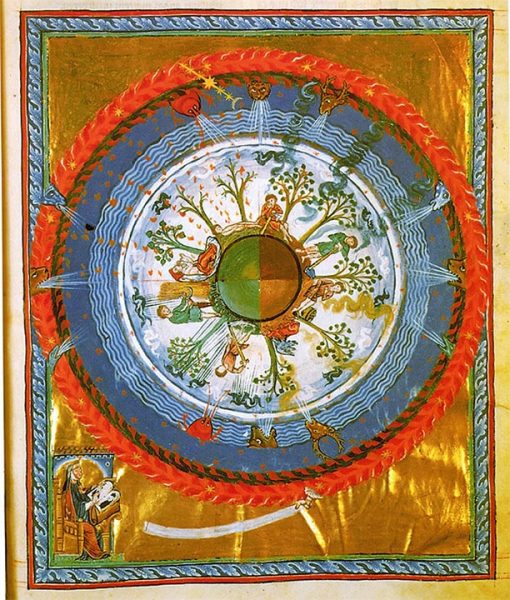

Liber Scivias was destined to become widely read, as she presented her unique cosmology by explaining the workings of the physical universe using a spiritual allegory based on Greek tradition. The earth, Hildegard maintained, was a sphere composed of the four elements—wind, fire, air, and water. Surrounded by layers of air and water, it was encased in an egg-shaped universe with an external “shell.”

The Earth itself was composed of the four elements, which are represented, curiously unequal in proportion and shape. Their arrangement is not orderly, and this very disorder illustrates one of Hildegard’s fundamental doctrines regarding the relation of this world to the universe. Before man’s fall, the elements were united in a harmonious combination, and Earth was Paradise; after that catastrophe, the harmony of the universe was disturbed, with the centre of all the trouble on this planet which has ever since remained in its now-familiar state of chaotic confusion or mistio, as Hildegard’s age called it. This mistio she represents vigorously enough by the irregular distribution of the elements over the Earth. “Thus mingled will they remain until subjected to the melting pot of the Lord Judgment, when they will emerge in new and eternal harmony, no longer mixed as matter, but separate and pure, parts of a new heaven and a new Earth.”

Beyond this are four outer zones belonging to the four winds, indicated by the breath of supernatural beings. They also correspond confusedly to the four elements and to the four regions of the heavenly bodies. The first is the aer aquosus, corresponding to water, and containing the east wind. In its outer part float clouds, expanding, contracting, and being blown this way and that, thus concealing or revealing the heavenly bodies. Then there is the purus (pure) aether, or zone of air, and containing the west wind. Of all the zones it is the widest, and the long axis of this zone and the remaining outer zones is from east to west, thus fixing the path of movement of the heavenly bodies.

It carries in it the constellations of the fixed stars, the Moon, and the two interior planets, Mercury and Venus. Beyond the zones of east wind and water and of the west wind and air are the umbrosa pellis, or ignis niger, the zone of the “dry” and the “earthy,” of the north wind, thunder, lightning, and storms. It is a dark, narrow shell which is the storehouse of “the treasures of the snow and of the hail.” The outermost shell is the lucidus ignis, zone of fire, of the south wind, and of the three outer planets, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn also, in Hildegard’s first scheme, of the Sun.

From all these zones with all their contents, elements, winds, Sun, Moon, planets, fixed stars, and the great animals or qualities of the heavens, are rained down influences upon the figure of the macrocosm. Hildegard tells the complete theological story of God and man and how everything is linked through the elements. Her scientific views were derived from the ancient Greek cosmology of the four elements, fires, air, water, and earth, with their complementary qualities of heat, dryness, moisture, and cold. The Book of Divine Works, a later magisterial work laid out a systematic mechanics and meaning of the cosmos.

In between writing her book, a vision moved her to found a new monastery in Rupertsberg. In her new monastery, she dedicated herself to writing more books on physics and medicine until 1158 and to finishing her musical collections. These collections are still popular today, and between 70 and 80 of her compositions have survived, which is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. In 1165 she founded a second monastery in Eibingen.

The picture to the left/above for mobile people depicts Hildegarde’s unique view of the Earth and its changing seasons. A purus (pure) aether contained stars, the moon, and other planets, which were immobile. An inner “fire” or energy source generated thunderous lightening and hail, while an outer fire fuelled the sun. Winds within this contained universe caused movements of clouds and resulted in seasonal changes on earth.

Hildegard von Bingen was a prolific communicator. More than three hundred of her letters survive today. One could probably sum her up as a mystic, scholar, musician, and botanist, a nun and a teacher with a unique perspective of the world and the origin of the surrounding universe and how man is interwoven with everything. Her egg-shaped universe is interestingly close to the heliocentric system, which is fascinating in itself.

The minor planet 898 Hildegard is named for her. It was discovered by Max Wolf in Heidelberg on the 3rd August 1918

Her Works:

- Liber Divinorum Operum, on cosmology, anthropology and theodicy.

- Liber Simplicis Medicinae o Physica, on the curative properties of plants and animals from a holistic perspective.

- Liber Compositae Medicinae o Causae et curae, on the origin of illnesses and their treatments from a theoretical perspective.

Credit Info Sources ‘The Scientific Views and Visions of Saint Hildegard’, by Charles Singer, Wikipedia, Pinterest, World History.com and Mediaevalists.net.