The Beagle And The Ghoul

The road to Mars, much like the surface of the red planet itself, is lined more with failures than good intentions

Mars has been so enthusiastic about scuppering the various probes and landers that a Great Galactic Ghoul was suggested by a journalist in 1997 to explain the struggles. Living on Mars, the ghoul is waiting to devour unsuspecting spacecraft. The ghoul exists for a reason; the history of Mars exploration is a story mired in misadventure.

Without listing all 50- something spacecraft that have been sent in the direction of our celestial neighbour, approximately half have failed. Between 1960 and 1971 alone there were at least a dozen failed missions. It wasn’t until 1971 that a Mars lander transmitted anything from the surface — and it lasted 14.5 seconds before contact was lost to the ghoul.

Things started looking up, and in 1996, NASA’s Sojourner rover even became the first rover on another planet — operating for nearly 90 days. By the ’00s, despite some notable failures from the Japanese Nozomi orbiter, NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter, the Mars Polar Lander, and the Deep Space 2 penetrators, it really started to seem like anyone could do this whole Mars spacecraft thing.

Enter The Beagle

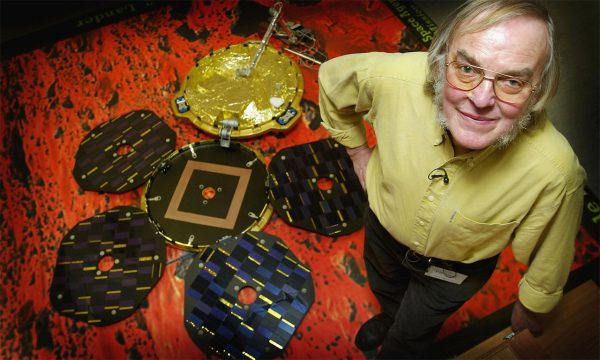

In 2003, Britain’s Beagle 2 launched aboard the ESA’s Mars Orbiter on a mission to search for signs of life, past or present — optimistically named after Charles Darwin’s famous vessel. Conceived and designed and developed by various British academics and companies, Beagle 2 was more famous and more popular than the Queen’s corgis.

So high profile was Britain’s Beagle that it even had music composed for it by Blur to be the mission’s callsign, and a painting from the artist Damien Hirst that served as a test card to set up the lander’s cameras and spectrometers after landing.

It couldn’t have been more British if the poet laureate Andrew Motion had written a five-part poem to be performed by the Queen as part of her traditional broadcast.

A Christmas Present

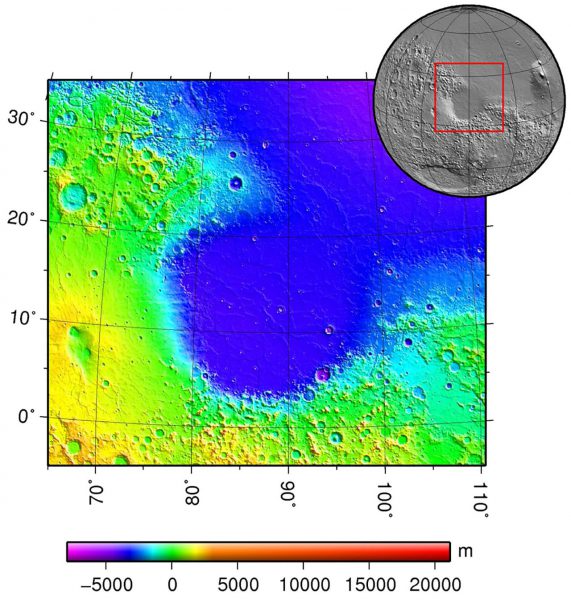

The Beagle was “released” a trajectory towards Mars on Dec 19, in much the same way as a bullet is “released” towards a target: entering the Martian atmosphere at 20,000 km/h.

Expectations were high, and it seemed fitting that the Beagle descended through the atmosphere on December 25 — a British spacecraft finding proof of life on Mars would have been a gift. The faithful Beagle was protected by a state-of-the-art heat shield, gently lowered by parachutes, and cushioned by airbags. Or, at least, it should have been.

There was no way of knowing if one, or more, of these, failed — because when called, the Beagle wouldn’t “speak”. Various commands were presumably tried by NASA’s Mars Odyssey as it passed overhead, including shake and roll over, but the Beagle didn’t obey. The 76-metre radio telescope dish at the Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK couldn’t get the Beagle to fetch a reply.

Luckily, the Mars Express spacecraft was designed and tested to transmit and receive signals from Beagle 2 — despite sounding more like an animated movie with Tom Hanks. Mars Express dutifully flew over the rover’s landing site, but the only thing this Beagle would do was stay.

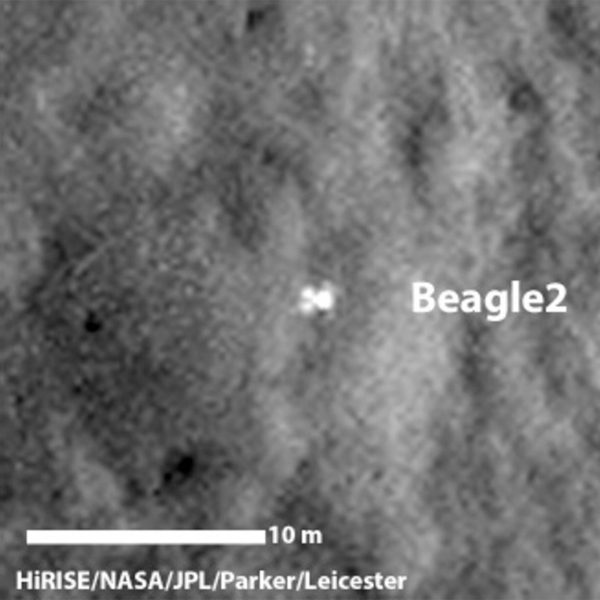

A Beagle’s fate

Beagle 2 was declared lost in February 2004, and it would be more than a decade before its fate was known. In 2015, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter identified the rover in high-res images. Beagle’s parachute and airbags had worked as planned — something that is never a given — and it had even started to deploy its solar panels. Unfortunately, this Beagle chose to “sit” before all four panels were uncovered — and its antenna didn’t ever manage to get the power to transmit or receive any signals.